Editor's note: More than 700 years ago, a ship loaded with porcelain sank off the coast of southeast China's Fujian province during a voyage overseas.

The wreckage of this Yuan dynasty

(1271-1368) vessel was found 30 meters underwater in 2010, near the islet of Shengbeiyu in Fujian. The salvage work began in 2022, with archaeologists having so far retrieved about 20,000 items, among which over 17,000 are Longquan celadon.

But, where was the ship going? Why was it loaded with so much porcelain? Were the items made as commodities? Who made them? And what exactly is Longquan celadon?

Based on archaeological findings at an ancient port about 700 kilometers away in the eastern Chinese city of Wenzhou, Zhejiang province, as well as some highly similar porcelain items discovered in Southeast Asia, experts concluded that the vessel is likely to have been a merchant ship traveling from Wenzhou to Southeast Asia.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, the Yuan dynasty authorities encouraged overseas trade, and the Longquan celadon industry was prosperous at the time, accounting for a large part of ceramic exports. Historical documents show that Wenzhou was a major port for exporting celadon, which was also sold to Africa and Europe.

Longquan, a small town in ancient times, refers to today's mountainous Longquan city in east China's Zhejiang province. Produced in this area and achieving fame across the world, Longquan celadon is a type of green-glazed Chinese porcelain with a history of 1,700 years, beginning in the 3rd century.

Although it originated during the Jin dynasty (265-420), Longquan celadon was not produced on a large-scale until the late 10th century during the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127). Since the 10th century in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (907-960) period, Longquan celadon was often selected as tribute gifts for emperors and royal families.

Later in 1138 in the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), the emperor moved the capital from north China to the southern city of Hangzhou, close to Longquan. The relocation was due to wars and political instability, resulting in a great number of people also travelling south. Among them, there were many skillful porcelain craftsmen and large-kiln owners, who integrated their techniques and businesses with locals, significantly boosting the local celadon industry. As such, Longquan celadon manufacturing quickly reached its peak of development and the area became the center of the porcelain industry.

In the following Yuan dynasty and early Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Longquan celadon continued to develop, with some masterpieces from that time surviving to the present day. From the mid to late Ming dynasty, its production experienced a decline due to major social changes and the emergence of new types of porcelain, such as Jingdezhen ceramics. When China began its reform and opening-up in 1978, Longquan celadon once again regained its momentum.

In 2006, traditional firing techniques of Longquan celadon were selected among the first batch of China's national-level intangible cultural heritage. Three years later, the techniques were also inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2009.

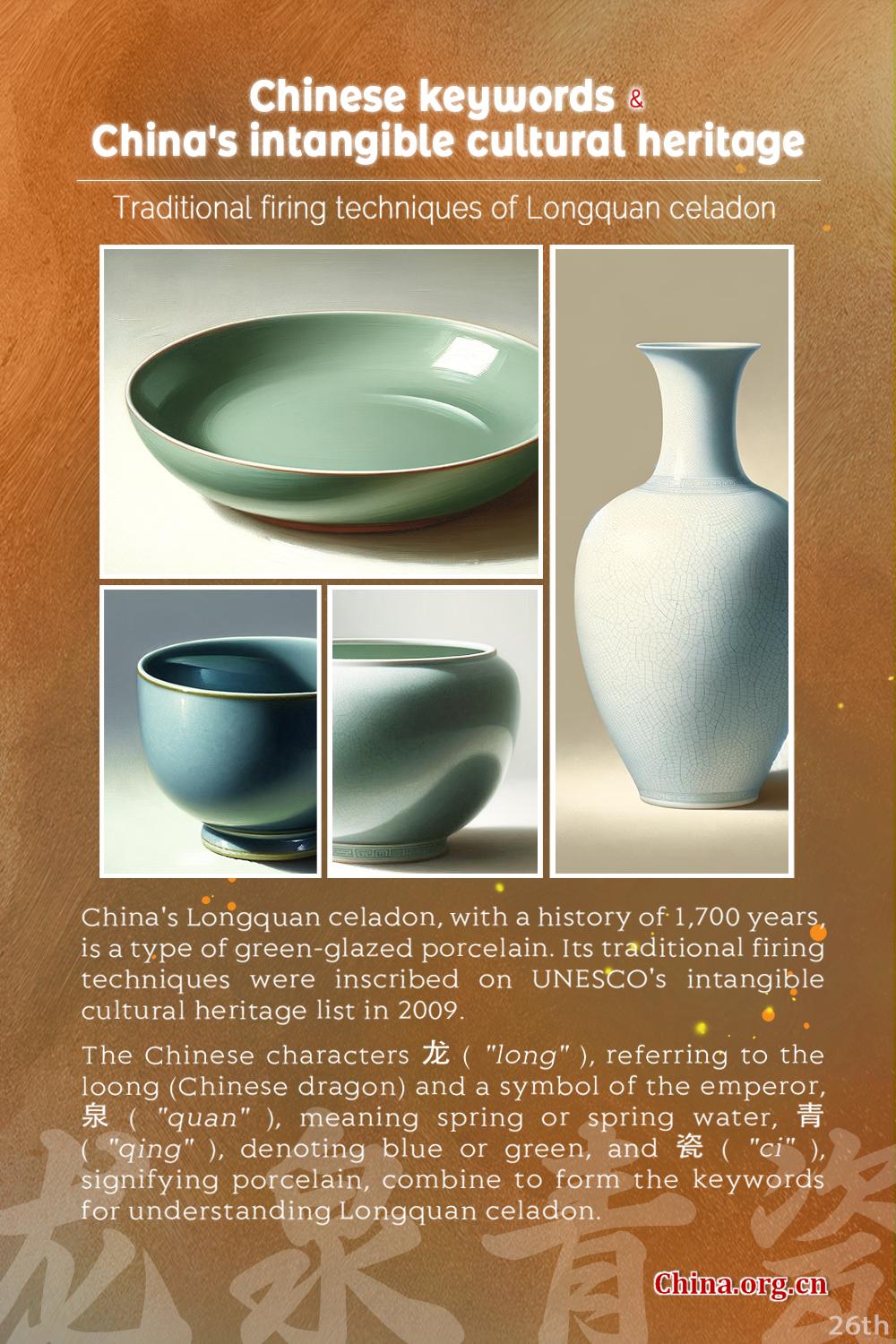

The Chinese characters 龙 ("long"), referring to the loong (Chinese dragon) and a symbol of the emperor, 泉 ("quan"), meaning spring or spring water, 青 ("qing"), denoting blue or green, and 瓷 ("ci"), signifying porcelain, combine to form the keywords for understanding Longquan celadon.

Longquan has deep forests, high mountains, clear rivers and smooth waterways, providing the necessary fuel, raw materials, water and transportation access for the porcelain business. Traditionally, craftsmen used local materials such as violet-golden clay and a mixture of burnt feldspar, limestone, quartz and plant ash to make celadon.

The production process mainly consists of ingredient mixing, molding, shape refining, decorating, glazing and firing. Thick glazed products require several layers of glaze, which are fired in a repeated cycle of heating and cooling four or five times, leaving 10 or even more layers. The firing temperature may reach as high as 1,310 degrees Celsius, as temperatures higher than 1,250 degrees Celsius will help produce the best jade-like green or blue colors.

Longquan celadon is usually classified into two styles: "elder brother" celadon and the "younger brother" variety. The story goes that two brothers during the Southern Song dynasty developed the two types. However, there is a lack of specific historical evidence proving the tale. "Elder brother" celadon has a dark body and a crackle effect. The color of the glaze usually looks like cream or ivory tending to grey or brown, with little green in it. Meanwhile, the "younger brother" variety is known for its masterpieces in jade-like green, among which are the most treasured fenqing (light milky-green or blue) and meiqing (plum green) glazes. These colors come from iron oxide fired in the kilns while varying the firing techniques such as the control of the timing and temperature.

A piece of Longquan celadon made during the Southern Song period is one of the most valuable items in Zhejiang Provincial Museum. The boat-shaped water dropper, a device used in ancient China to add water on inkstones when grinding ink sticks, is 16.2 centimeters long, 6.5 cm wide and 9.1 cm high. It features carved columns, a pavilion and a shelter. Two passengers seem to be chatting inside the pavilion, and the boatman looks to be reaching for his bamboo hat which is on the roof, while his robe flows in the wind.

Cai Naiwu, a ceramics expert at the museum, explained that this unique celadon water dropper is particularly exquisite, showcasing a high level of Longquan celadon manufacturing. The item was probably custom-made for a member of the literati, which was a common practice at the time.

Longquan celadon was not used only by the imperial family in ancient times, but also by ordinary people. Large kilns were able to produce sufficient quantities of items for use in the home, containing no harmful substances like lead or cadmium. Nowadays, ancient Longquan celadon masterworks are still treasured by museums and collectors, while modern celadon wares are commonly used in daily life. Leaders of the Chinese government also often choose modern celadon items as traditional and valuable presents for foreign dignitaries and friends.

In 2018, the first World Celadon Conference was held in Longquan city, attended by ceramic experts, master craftspeople, enterprises and government officials from 12 countries, including Australia, Germany, Japan, Norway, South Korea and the United States. This October, the sixth edition kicked off, hosting forums and seminars to discuss inheritance and innovation in the industry. An exhibition titled "Longquan City Celadon Art" was also held earlier this year at the China Cultural Center in Brussels, Belgium, with 55 works made by Chinese artists on display.

Discover more about China's intangible cultural heritage and their keywords:

Items/years inscribed on UNESCO ICH list:

• 2022: Traditional tea processing

• 2020: Wangchuan ceremony, taijiquan

• 2018: Lum medicinal bathing of Sowa Rigpa

• 2016: Twenty-four solar terms

• 2013: Abacus-based Zhusuan

• 2012: Training plan for Fujian puppetry performers

• 2011: Shadow puppetry, Yimakan storytelling

• 2010: Peking opera, acupuncture and moxibustion, wooden movable-type printing, watertight-bulkhead technology of Chinese junks, Meshrep

• 2009: Yueju opera, Xi'an wind and percussion ensemble, traditional handicrafts of making Xuan paper, traditional firing techniques of Longquan celadon