The "Cheng'an Baohuo" silver coin of Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) is displayed at the Jin Shangjing History Museum in Harbin, northeast China's Heilongjiang Province, June

At the Jin Shangjing History Museum in Harbin, capital of northeast China's Heilongjiang Province, a gleaming thumb-sized silver coin attracts curious visitors. With unique curved edges unlike other Chinese and Western coins, the silver money in the shape of a double-bit ax tells its remarkable history.

The silver money minted by the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) government was the first official currency made of silver in Chinese history, said Hu Zhiyuan, director of the interpretation department of the museum.

The engraved traditional Chinese characters on the silver indicated its information, with "Cheng'an" representing the name of the era (1196-1200) and "Baohuo" meaning currency, said Hu.

The institutions in charge of forging money and its central government management agency were also inscribed on the silver.

Hu said the piece's unique appearance and its Chinese inscription reflected the influence of traditional Chinese culture in the Jin Dynasty, showcasing the integration of different ethnic cultures during its century-long reign.

The Jin Dynasty, founded by the Jurchen people, ruled over northern and northeastern China, coexisting with the Song, Liao, Yuan, and Western Xia regimes that controlled parts of the country during the historical period.

Hu explained that the Jurchens initially lived by fishing and hunting and bartered within their tribes for a long time. However, as trade between the three peoples grew, they soon began using bronze coins from the Liao and Song dynasties ruled by the Khitan and Han people.

In 1125, after the Jin regime overthrew the Liao regime and advanced southward into the Song territory, a significant influx of currency and craftsmen from the southern part of China reached Jin's heartland, leaving profound impacts on its own monetary system, according to Hu, adding that the shape and the layout of the Chinese inscriptions of some coins from the Song and the Jin dynasties are similar -- another sign of ethnic integration.

Hu said that during the century-long interactions between the Song and Jin dynasties, peace prevailed for over 60 years, with the trade of fur, ginseng, tea, and textiles flourishing through designated border markets. Peculiar silver coins and ingots of the Jin Dynasty were used and then carried across China.

"Through such ingots discovered in what is Lintong District now in northwest China's Shaanxi Province, researchers can see close economic and trade exchanges between the Jurchen and other ethnic groups in different regions of China," said Hu.

As the ice and snow resources have brought more and more tourists to Harbin, an increasing number of visitors are flocking to the museum, delving into the lesser-known stories of the Jurchen and other northern Chinese ethnic groups through these relics.

Mu Changqing, deputy director of the museum's cultural relics preservation department, said the museum welcomed nearly 180,000 visitors from January to June this year, with a maximum of 15,023 visitors in a single day.

The museum plans to provide multimedia displays, replicate historical scenes, and organize educational lectures so visitors can better learn about the history of the Jin Dynasty and the cultures of different ethnic groups.

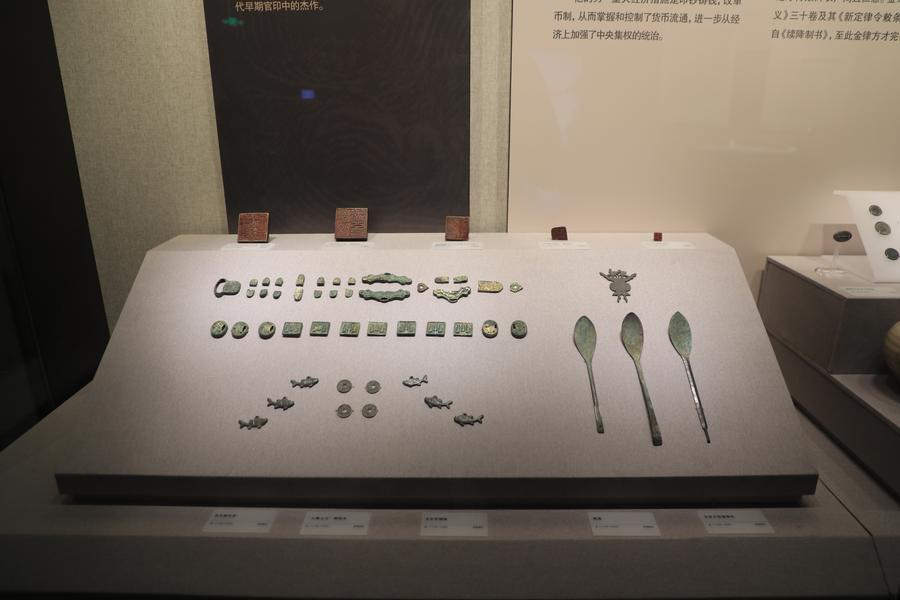

Various coins and cultural relics exhibits of Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) are displayed at the Jin Shangjing History Museum in Harbin, northeast China's Heilongjiang Province, June 26, 2024. (Xinhua/Tang Tiefu)